LIST OF ARTICLES – PAGE 1 (this page)

| The Oregonian (OR) 2000, 2001, 2010 | Just Out (OR) 1999, 2008 |

| Citysearch (OR) 1998, 2001 | Earth Island Journal (CA) 2001 |

| The Portland Tribune (OR) 2001 |

LIST OF ARTICLES – PAGE 2 (cont.)

| The Oregonian (OR) 1997 | Portland Songwriters Assoc. (OR) 1996 | The Women’s Journal (OR) 1997 |

| The Voice Magazine (CO) 1992 | Omaha World Herald (NE) 1995 | Indie-Music.com (IN) 2001 |

Just Out

Hooves and Flippers

– by Rebecca Ragain, Just Out Magazine, February 2008

Portland singer/songwriter adds animal documentaries to list of accomplishments

If you lived in Oregon a decade ago—or even if you didn’t—you probably heard the news when Keiko the orca, the star of the movie Free Willy, was relocated to the Oregon Coast Aquarium. You may even know that Keiko was later returned to his native waters in Iceland in 1998.

If you lost track of Keiko after that, you’re not alone.

That’s why Theresa Demarest, a Portland lesbian musician and budding filmmaker, is so excited to tell Keiko’s story.

Demarest is engrossed in the production of “Keiko’s Dream…Keiko’s Legacy,” a 15- to 20-minute educational DVD about his five years in the wild.

“The movie we’re doing with Keiko is a story that hasn’t been told,” she says. “We get to tell the story and show people footage of him swimming free, looking for a mate, interacting with wild orcas.”

She continues: “Most people don’t even know what happened to Keiko, and it’s powerful, really powerful, what happened.”

Demarest has followed Keiko’s story since he was moved to Newport in 1996. At the time, she was confined to bed because of complications related to a bout with breast cancer. It was her second run-in with the disease.

“I was very ill, and all I could do was watch television,” she recalls. “I became mesmerized with the story.”

Inspired by Keiko’s strength, Demarest wrote a song called “Keiko’s Dream.” That in turn led to Keiko’s Dream Tour, a series of grant-funded and sponsor-supported concerts/presentations during which she and her band performed and ocean conservationists spoke about the famous orca.

When 27-year-old Keiko died in 2003, the Free Willy-Keiko Foundation asked Demarest to put together a film honoring his life. But for a number of reasons, the project didn’t happen until now.

“There were a lot of bigger players vying to put out big documentaries about Keiko’s life,” says Demarest, who at the time chose to walk away from the film contract and the political quagmire surrounding it.

Four years later, no one had made a film. Groups including the Free Willy-Keiko Foundation, OrcaLab and independent videographer Eric Engleton decided to send their footage to Demarest so she could go ahead with the project.

Although there is still a chance that her film could stir up the controversy between the various groups involved in Keiko’s life, she is not letting that slow her down. “I feel like I’m just like the average person: I don’t care about those guys…I care about this,” she says, gesturing to a computer screen displaying footage of Keiko swimming free.

So now Demarest spends hours each week poring over footage of Keiko, piecing together his end-of-life story and setting the scenes to her own music. The work is time-consuming and meticulous, but she loves it.

Demarest plays a five-second bit of footage on the computer and explains how it has taken her hours to get the timing of the accompanying music just right: “Just that little thing, that’s like creating a piece of artwork.”

“I get to take film and my music to tell an epic story,” she says, sounding awestruck. “Wow! Oh my God, that’s wonderful!”

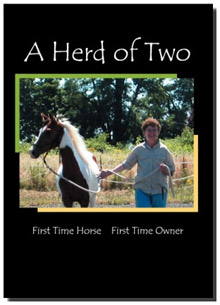

This isn’t the first time Demarest, who is mainly recognized as a professional musician, has ventured into filmmaking. She spent the past couple of years producing and editing her first film, a 26-minute documentary called “Herd of Two: First Time Horse, First Time Owner.”

This isn’t the first time Demarest, who is mainly recognized as a professional musician, has ventured into filmmaking. She spent the past couple of years producing and editing her first film, a 26-minute documentary called “Herd of Two: First Time Horse, First Time Owner.”

The idea for “Herd of Two” originated about three years ago, when Demarest fell in love. Her partner of two decades probably wasn’t too jealous, though, because the recipient of Demarest’s affection was a 6-month-old filly.

In response to a newspaper ad promoting riding lessons, Demarest had trekked out to a barn in Canby. It was there that she first saw the little horse that she bought and named Tehya Takoda, or Precious Friend.

“I had never been around horses before, ever,” says Demarest. “It was a crazy thing to do, but I didn’t know that. I just fell in love with her.”

“Herd of Two” documents Tehya’s development as she grows from a filly to a young mare. The film focuses on the training style called natural horsemanship, which Demarest is studying extensively.

“In natural horsemanship, you have to learn the psychology of horses,” she says. “You have to learn how to communicate with them.”

Demarest’s studies fueled her enthusiasm for her horse, which she describes as “stunningly intelligent and beautiful.” She likes to say that if you were to throw a Rubik’s Cube to her horse, Tehya would solve it in less than 30 seconds, “throw it back and say, ‘Now give me something hard.’ ”

Tehya is half Arabian, an ancient breed known for its sensitivity, intelligence and endurance, and half American Saddlebred, a breed that some call the ultimate show horse.

Because Tehya is young, energetic and strong, riding her is a challenge for Demarest, who jokingly describes herself as ancient. In addition, both horse and rider are relatively “green,” or inexperienced.

“There’s a saying: Green on green makes black on blue,” says Demarest with a grin.

So for now, Tehya and Demarest are mostly learning their roles as mount and rider separately. Professional trainers are working with Tehya, while Demarest learns to ride on more experienced animals.

Demarest is producing a follow-up movie to “Herd of Two.” It will chronicle her journey into horsemanship, which hasn’t been an easy one.

“I get on the horse, and as soon as the horse starts to go, I get scared,” she says.

Demarest, who was told 20 years ago that she had only six months to live, is in great physical shape these days. But she risks her body every time she gets on a horse, which most people in their late 40s or 50s would probably agree is a bit scary.

But Demarest perseveres, lifting weights and taking aerobics in order to stay fit enough to ride her young horse. “I spent the whole first year crying my eyes out, but now I’m cantering bareback and doing pretty well,” she says.

Still, it will be a while before Demarest is comfortable riding Tehya. When she reaches that point, she will be able to wrap up the second movie.

During this flurry of filmmaking, Demarest has not been performing live as often as she has in the past. She is still an active songwriter and musician—in fact, she is writing another album—but filmmaking takes up much of her time and resources.

For instance, she is searching for a sponsor to support a live studio recording of the music for “Keiko’s Dream…Keiko’s Legacy.”

Demarest does miss performing, so whenever the right invitation comes along, she and her band, Good Company, are likely to accept. In September, they performed at In Other Words bookstore’s Luna Music Series and did a live show for KBOO-FM’s WomanSoul program.

Whether performing live, writing songs or recording soundtracks for film, Demarest says music will always be part of her life. “Music is one of the many reasons why I’m still sitting here today.”

View trailers for “Keiko’s Dream…Keiko’s Legacy” and “Herd of Two” and purchase Theresa Demarest’s DVDs and CDs at www.theresacd.com. Single songs can be downloaded from iTunes.

Rebecca Ragain is a Portland freelance writer whose family used to raise and train Tennessee Walking Horses. Contact her at www.rebeccaragain.com.

KEIKO’S DREAM: An Orca’s Tribute

By Katy Muldoon – The Oregonian, February 2001

Theresa Demarest came eye-to-eye with the famed whale and came away with a mission

Jefferson High School’s auditorium shivers like a little slice of Iceland.

But here comes the heat.

Teen-age boys and girls wrapped in sweat shirts and parkas yank open the heavy doors, shimmy into the stiff wooden theater seats and start chair dancing. Swaying. Clapping. Shouting “Sing it, girl!” and “Oh, yeah!” and “Free Willy!”

Free Willy?

Yes, that Willy — star of surf and screen who, even two years gone from Oregon, can draw a crowd.

Keiko, the orca formerly known as Willy in the 1993 Warner Bros. Film “Free Willy”, is not, of course, on stage at Jefferson High School this frigid February day. It just sounds as if he is when electric guitar riffs squeal in a remarkably realistic rendition of whale vocalizations. When the drums tap-tap-tap the clicks of an orca call. When piano notes whisper, crest and crash, like a killer whale breaching at sea.

Together, they form an instrumental jazz tune called ‘Keiko’s Dream.” Together, they illustrate Theresa Demarest’s awakening as a musician with a message — a singer-songwriter who yearns to be a voice for the oceans and, especially, a voice for Keiko.

Long after most Northwesterners have filed the famous whale’s story away in their memory banks, Demarest and her band, Good Company, continue to push the save-the-whale agenda in a series of concerts and environmental education presentations in Portland-area schools and performance halls.

At 7 p.m. Friday, they will perform a free concert for students and the public at Brooklyn/Winterhaven Elementary School in Southeast Portland. Mark Berman of San Francisco’s Earth Island Institute, which was instrumental in rescuing the once-ailing killer whale from a Mexico City amusement park, will be guest speaker.

“Our intention is to move people”, Demarest says. “Their hearts. Their minds. Their feet.”

Keiko had that effect on Demarest, swimming into her consciousness in 1996, the year the orca film star moved to the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport. There, he was tended to by eager animal lovers intent on restoring his health and returning him to the sea in Iceland, where he was captured more than two decades ago.

Demarest watched the whale story unfold from her own sickbed. As she coped with a grim prognosis and breast cancer treatments that left her wretchedly ill, there on television was a story of healing and hope — ideas she ached to embrace.

When she was strong enough, she drove to the aquarium to see for herself through the underwater windows separating the public from the beast. There, she had one of those experiences not uncommon during Oregon’s Keiko days: “he came right up to me,” she recalls. “He seemed to make eye contact.”

Demarest nodded her head. Keiko nodded his. Demarest turned her head to one side. Keiko turned his. The whale raced across his pool, then returned to face her. She stared. He nodded.

She returned home that day and began writing “Keiko’s Dream,” which “evokes the whale’s cry for freedom,” she says.

In 1999, it became the title song for a compact disc she recorded live during a concert at the Portland Center for the Performing Arts and produced on her own small label, Joshua Records. Her band includes such longtime Portland musicians as Tim Ellis, Janice Scroggins, Patrick Lamb, Byron Mercurius and Joe Conrad.

Since then, Demarest’s Keiko gig has blossomed into the sponsor- and grant-funded educational concert tour that took her to Jefferson High earlier this month and that will continue this week. The tour is supported by the Regional Arts & Culture Council, among other organizations.

Demarest — a former nun, retired critical-care nurse and mother of a grown son –has regained her health and refocused her life so that music hums at its core.

Jazz. Blues. Neo-folk. Fusion.

And orca. Especially orca.

THERESA ON: PERFORMING

“Performing is the perfect moment, when you send out your best and most attentive energy. In the most perfect of these moments, it comes back to you, like lightening; powerful, immediate, and unmistakable. It’s the gift your audience gives back to you.”

Keiko Update

Keiko’s keepers sound as optimistic as NBA coaches with their sights on the playoffs: “He’s healthy, eating well, active and responsive. We’ve noticed some aggressive behavior…,”Charles Vinick says. “We hope to be out by May.”

Vinick, of Ocean Futures, the organization that cares for the star of the 1993 Warner Bros. Movie “Free Willy”, is optimistic that the whale might swim to freedom by summer. By ‘out”, he means out of the enclosed bay where the whale lives in Iceland’s Westmann Islands.

Last summer, keepers reintroduced Keiko, who is about 24, to the open ocean for the first time since he was captured off Iceland in 1979. The whale, who lived at the Oregon Coast Aquarium from 1996 to 1998, is trained to follow a boat.

In 2000, he swam 500 miles, ventured near wild whales 19 times and appeared to come into contact with five times.

Keepers hope to acquire a bigger boat that will allow them to stay offshore with him for weeks at a time, so that this summer they can follow pods of wild whales that migrate through the area.

They’re working to refine the satellite transmitter the whale will wear at sea, so they can track him for as long as possible, should he decide to swim free.

Meanwhile, Vinick says, “We see him acting like a wild whale, and that’s what we’re looking for.”

A Rock’n’Roll Orca-stra

Earth Island Journal, Summer 2001

In February, Mark Berman flew to Oregon for a rock’n’roll show that shook the walls of two concert halls in Portland. Mark wasn’t playing the drums or electric guitars, however. He was the featured speaker on Keiko’s Dream Tour — a unique eco-rock road show developed by Joshua Records and its award-winning band, Theresa Demarest & Good Company.

In February, Mark Berman flew to Oregon for a rock’n’roll show that shook the walls of two concert halls in Portland. Mark wasn’t playing the drums or electric guitars, however. He was the featured speaker on Keiko’s Dream Tour — a unique eco-rock road show developed by Joshua Records and its award-winning band, Theresa Demarest & Good Company.

It all began several years ago, when singer/songwriter/producer Theresa Demarest was recovering from breast cancer. During her painful recovery, Demarest (a former nun and retired critical-care nurse) changed to see a TV documentary on Keiko’s remarkable journey from captivity in a Mexican theme park to a custom-built recovery tank at the Oregon Coast Aquarium. Demarest credits this story of healing and hope with helping her survive cancer. The experience left her committed “to participate in the world in a renewed and more committed way.”

During her illness, Demarest had written an instrumental piece, but it lacked a voice. With her cancer in remission, Demarest realized that her composition not only had a voice, it had a title –“Keiko’s Dream.”

Drawing on the squealing guitar riffs of band member Tim Ellis, Demarest produced a remarkably realistic rendition of whale vocalizations. With Good Company’s drums tapping out the clicks of an orca call and Demarest’s piano keys creating and crashing, it sounds as if Keiko were right on stage.

“Our intention is to move people — their hearts, their minds and their feet.” Demarest says. The music is intended to make listeners ask ‘how you fit into the scheme of life on this planet.”

Demarest and Joshua Records agreed to release Good Company’s live concert CD, Keiko’s Dream, with proceeds from sales benefiting the Ocean Futures Society (formed from a merger between the Free Willy Keiko Foundation and The Jean-Michel Cousteau Institute). Joshua Records also launched the Keiko’s Dream Tour concerts.

Good Company’s program of jazz/blues/folk/fusion culminates with a performance of “Keiko’s Dream.” After a speaker from Joshua Records calls on the audience to become a “voice for the ocean,” Mark Berman offers a slide-lecture recounting Keiko’s escape from captivity (a task in which Earth Island Institute was instrumental) and brings folks up-to-date with recent slides of Keiko swimming free in his home waters off Iceland.

DECISION TIME FOR KEIKO’S KEEPERS

By Katy Muldoon – The Sunday Oregonian, September 2, 2001

After spending millions to help the famed whale, his benefactors must make plans for what to do if he never returns to life at sea.

About one year ago, Michael Hutchins advised Keiko’s keepers that they would be wise to begin preparing the public for a hard message: failure.

Hutchins, director of conservation and science for the American Zoo and Aquarium Association, wasn’t certain that the effort to set the famous whales free would flop. But he thought that so many people around the world had invested their money and emotions in the whale’s tale that keepers owed it to them to lay Keiko’s chances on the table.

Problem was, Ocean Futures Society, the nonprofit environmental organization that cares for Keiko, had no idea whether the whale that had been hand fed for two decades would ever join a pod of wild orcas, swim off into the sunset and survive.

They still don’t.

But because the “Free Willy” star failed to make the break for freedom this summer, Oceans futures may have to concede that Keiko’s future will be a captive or semicaptive one.

“This is not a Hollywood movie,” Hutchins said last week. “This is a real animal in a real situation. It’s real people trying to deal with the ethical questions…

“The solutions are going to have to be based on what’s best for Keiko under the resource limitations that the organization has.”

It’s possible that the eight-year, multi-million dollar effort to return the movie-star whale to life at sea with his own species is over.

The killer whale’s keepers announced last week that Keiko is back in a netted pen in Iceland for the winter. Trained to follow his crew’s boat to sea, he spent much of the summer swimming in the North Atlantic Ocean near wild whales.

“It’s premature to say what we’ll decide,” said Charles Vinick, executive vice president of Ocean Futures.

In the months ahead, keepers and benefactors must determine:

- If, to the best of their knowledge, Keiko ever will be capable of surviving at sea without human help. He has not yet shown that he can feed himself.

- If wild whales ever would accept him into their close-knit society, about which little is known. Although he often swam near orcas this summer and last, keepers have seen no evidence of bonding. Neither have they seen aggressive behavior toward Keiko.

- If it makes sense to continue to pay for the project that, to date, has cost an estimated 23 million. In the past two years, with summers spent at sea, the cost has run about 3 million annually.

- If continuing the reintroduction effort is in the whale’s best interest. And if it’s not, they’ll have to decide not only how Keiko should live out his days, but also where.

Keepers expect that a salmon-farming operation will be built near Klettsvik, the picturesque bay where the whale’s floating pen is anchored. The fisheries industry makes Iceland’s economy tick, and the farm would take precedence over the resident whale. Whale keepers worry that the operation could compromise water quality in the bay and make it an unhealthy place for Keiko.

Construction of the farm has been delayed at least until next spring so Ocean Futures has the winter to consider whether it will keep Keiko there of move him.

One Big Experiment

Keiko’s keepers sound as optimistic as NBA coaches with their sights on the playoffs: “He’s healthy, eating well, active and responsive. We’ve noticed some aggressive behavior…,”Charles Vinick says. “We hope to be out by May.”

Vinick, of Ocean Futures, the organization that cares for the star of the 1993 Warner Bros. Movie “Free Willy”, is optimistic that the whale might swim to freedom by summer. By ‘out”, he means out of the enclosed bay where the whale lives in Iceland’s Westmann Islands.

Last summer, keepers reintroduced Keiko, who is about 24, to the open ocean for the first time since he was captured off Iceland in 1979. The whale, who lived at the Oregon Coast Aquarium from 1996 to 1998, is trained to follow a boat.

In 2000, he swam 500 miles, ventured near wild whales 19 times and appeared to come into contact with five times.

Keepers hope to acquire a bigger boat that will allow them to stay offshore with him for weeks at a time, so that this summer they can follow pods of wild whales that migrate through the area.

They’re working to refine the satellite transmitter the whale will wear at sea, so they can track him for as long as possible, should he decide to swim free.

Meanwhile, Vinick says, “We see him acting like a wild whale, and that’s what we’re looking for.”

A Picture of Health

Even objective observers agree that the once sickly, underweight whale, who for years swam in a Mexico City amusement park pool too small and warm for an animal his size, appears better off today.

Hutchins, of the American Zoo and Aquarium Association, remembers flying in a helicopter last September above the Atlantic. Below was Keiko, swimming swiftly and powerfully behind his crew’s boat in the open ocean.

“It was spectacular,” Hutchins said. “It was remarkable the degree to which Keiko’s physical condition had improved. I was totally blown away by that.”

Hutchins was equally surprised that Ocean Futures had invited him to Iceland to assess everything from the reintroduction protocol, to research connected to the project, staffing, hands-on work with Keiko, public relations and fundraising.

- He had, after all, been publicly critical of the effort since its inception for two reasons shared by many:

- He thought that the enormous amount of money was ill spent on one animal, particularly one whose species is not endangered. Hutchins says that the estimated $20 million spent on Keiko during the project’s first seven years exceeded what the Wildlife Conservation Society, for instance, spends on 300 projects in 60 countries during two years.

- And he thought that even among captive killer whales, Keiko was a poor choice for reintroduction to the wild because he had spent so many years in close contact with humans.

- Keiko is the first long-captive killer whale ever reintroduced to the wild.

Zoos and aquariums across breed many endangered orthreatened species specifically so they can release themin nature. Keys to success, Hutchins said, involve training animals from birth for introduction to life in he wild, raising them in naturalistic environments and restricting interaction with people.

California condor chicks, for instance, are raised with hand puppets that look like condors, so the chicks will not bond with human caretakers.

Keiko, whose age is estimated at 24 or 25, was captured near Iceland about age 2. He spent most of his life performing for fans in marine parks and communing with keepers, who would swim with him, rub his tuxedolike belly and even ride the beast as if he were a surfboard.

Then, Keiko struck gold. He landed the title role in Warner Bros.’ Popular 1993 movie, “Free Willy.” In the film, do-gooders help an affable, ailing whale escape unscrupulous marine park owners.

After it hit theaters, the effort to return the real-life “Willy” to the sea ignited. The story got oceans of international publicity. Adults and schoolchildren near and far donated money. And life began to imitate art.

The Keiko Effect

The story is familiar to Oregonians, of course, because Keiko spent 32 months here in a fancy halfway house: a $7.3 million, 2-million-gallon tank custom-built for him at the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport.

From January 1996 to September 1998, more than 2.5 million visitors paid up to $8.75 a pop to gaze at him through underwater windows in his tank. Often, he would hang in the water, just inches away from the glass, and gaze back.

Aquarium visitors weren’t the only ones to relish Keiko’s charm. Animal-rights groups, particularly those who don’t find value keeping animals in zoos and aquariums, rode the wave of interest in the whale to champion their causes.

Howard Garrett, for example, stills holds up Keiko’s experience in Iceland as a shining example of his pet project: to persuade Maimi Seaquarium in Florida to return its captive killer whale, Lolita, to her home waters in Puget Sound.

Garrett is president of a Greenbank, Wash., environmental education organization called Orca Conservancy. Since 1995, he has worked to free Lolita, who is 35 or 36 years old.

“I really feel like she can get the spinoff effect from Keiko,” Garrett said, “…that she can grab the imagination and attention…

“It shows so much about animals in the natural world. It just revives faith.”

Faith – and some science.

Early in the project, Keiko’s keepers forged alliances with marine mammal researchers, some at such prestigious institutions as the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts. Over the years and as recently as this summer, scientists have used the project to collect data not only on Keiko, but also on the little-studied Atlantic killer whale population that migrates each spring and summer through Iceland’s Westmann Islands, where Keiko lives.

They have surveyed where the whales swim and feed, creating aerial maps of those locations. Shooting pictures galore, they have begun a photo-identification catalog of the population. They have collected blubber samples from nearly two dozen whales and will subject the samples to genetic testing.

Using underwater recording devices called hydrophones, researchers have collected acoustic data on the migrating pods; one thing they’ve learned is that Keiko’s vocalizations sound different from those of the wild whales.

Keepers, too, have collected behavioral data on Keiko since he moved to Oregon in 1996. And they continue to do so.

Some of that data include his inclination to follow boats. During his open-ocean forays this summer, Keiko was spotted following a fishing boat and a cruise ship that was dumping garbage.

On another occasion last month, he approached a small boat in which a bird hunter was cleaning his catch. The hunter claimed in Icelandic news accounts that Keiko swam up to his vessel and startled him. But when he saw the tracking device attached to the whale, the hunter realized it was Keiko, reached out and stroked his shiny black skin.

True or not, such accounts are likely to be part of the discussions around the Ocean Futures boardroom table this fall and winter, when keepers and the whale’s moneyed benefactors determine whether the experiment has reached the limits of science, finances and good sense.

Ocean Futures has promised to care for Keiko as long as he is in captivity.

“At some point,” said Bob Ratliffe, a spokesman for Craig McCaw, “you’ve got to say we’ve given him…an unbelievably life-enriching experience.”

Ratliffe and McCaw and others on the Ocean Futures board know one thing about Keiko’s future: They don’t want to return him to a concrete enclosure.

But other alternatives, including one in which Keiko would again be on public display, perhaps in a sea pen, are possible and would require much study in the year to come.

“I think,” said Hutchins, of the American Zoo and Aquarium Association, “that Ocean Futures has some heart-wrenching decisions to make.

HARMONY WITH LIFE GOES WELL BEYOND BASIC SISTER ACT

-by Melanie McFarland of the Oregonian staff , March 2000

Theresa Demarest has leapt a world of hurdles on her way to finding her life’s plan. The singer/songwriter’s music helped her escape the traumatic experiences of being the child of an alcoholic. She picked up her brother’s guitar and began to play, opening a door to personal sanctuary.

In high school and in a Mid-western convent, her music let her express her originality in the face of conformity. Her most memorable moment from that era was in the ’70s when she decided to become a nun. She took her guitar to a convent in Omaha Nebraska, and formed a band of sisters called “We People”. Included in their repertoire of original spiritual pieces were rocking covers of “California Dreamin'” and “Wipe Out”. Understandably, seeing nuns perform pop hits floored audiences every time.

After leaving the convent, she toured clubs, married, had a son with, and divorced fellow musician Tom Demarest and attended nursing school. Then, Demarest’s music gained her the victory of her life: she was able to prevail when cancer surfaced in 1983 and 1987.

In the recurrence, doctors gave her 14 months to live. Demarest thinks her music was the main force that helped her beat the cancer into remission.

Now, in the wake of her struggles, she feels more sure of herself that ever. Demarest has a firm grasp of what’s she’s supposed to do with her life.

“Before we’re born, I believe we all know exactly who we are, where we’ve come from and what we’re supposed to do on the Earth”, Demarest said. “We have the program, but when we’re born, we forget everything. So our job in life is to figure out who we are and why we are here… and at some point we become connected. I feel like right now, through these people around me and this music, I am connected to my original instructions. I didn’t get here by accident, it’s not something I just bumped into. I’ve been through a lot.”

Her new CD “MOON RISING”, released on her Label Joshua Records, struck numerous chords with listeners and critics around the Northwest and beyond. With the help of GOOD COMPANY, which includes guitarist Tim Ellis, Portland blues great Linda Hornbuckle, and acclaimed keyboardist Janice Scroggins, Demarest’s album puts heartfelt stories to the sound of jazz, folk, and blues-inspired tunes.

Her sumptuous voice is tinged with a country yodel and supported by tender guitar chords and keyboards that range from airy to energetic. The mixture makes for and enjoyable sound that leaves the listener wanting for nothing. “MOON RISING” also is getting airplay as far away as Carlsbad Calif where the disc jockeys of 95.7 KUPR-FM’ weekly show “Global Gig, became faithful fans after hearing about the artist’s triumphs, both in her life and her music.

“Her story was the first thing that drew me to her” said PJ Grimes, a writer and producer for the Global Gig show.”Her strength just stood out. She just wants to live. What a terrific role model for someone else. We always complain about the trivial things, but this woman was facing life and death. Her music is very heartfelt and warm, and it’s apparent that she’s doing what she needs to be doing. I just thought she’s perfect.”

Grimes included Demarest in an upcoming vegetarian cookbook PJ is putting together. The book, called “The Backstage Gourmet‘” tosses Demarest’s macrobiotic salad in with recipes by Keiko Matsui, Guns & Roses keyboardist Dizzy Reed and others.

Culinary contributions aside, Demarest hopes her music will help others pursue their life’s purpose, just as it has aided her in finding her own.

“Music has just helped me interpret life, helped me cope and resolve issues,” she said. “Love has to be expressed, fear has to be expressed, anger has to be expressed, or we’ll just rot. This is the way I express my feelings. Hopefully it’s helped other people too.”

LET THE GOOD TIMES ROCK AND ROLL

– Will O’ Bryan, JUST OUT, A&E Editor, Feb 1999

Theresa Demarest wraps herself in the healing power of music and finds her place in the world with a song.

Some visitors to Theresa Demarest’s Web site (theresacd.com) learn about Demarest’s accomplishments as a singer songwriter-musician. Some glean information about Keiko the killer whale, for whom Demarest seems to harbor a monumental affection. And some visitors may stumble across a gripping essay written by Demarest about her battle with breast cancer.

“When I finally did see the doctor…it was 2 centimeters by 4 centimeters by 6 centimeters too big,” she writes about the discovery of her first tumor in 1983.

A year later, following chemotherapy treatment and recovery, Demarest returned to school and became a critical care nurse. In 1988, everything seemed fine and she was even preparing to buy her first house.

“But then, one morning, there it was,” writes Demarest. “A tumor in my chest just sitting there. I could feel it – immovable, irregular edges. Big. Ugly. Terrifying. I took a friend to the doctor with me. I didn’t want to hear what I already knew. There was no question about it: my breast cancer had metastasized into my chest wall. The doctor diagnosed me with a life expectancy of 14 months and scheduled surgery for the very next day.”

Following the diagnosis, Demarest rediscovered her passion for music and wrote the song Bein’ Who You Are,” which she dedicated to her son.

Returning to music, says Demarest, gave her more than comfort and inspiration, though. She writes: “Seven months into my 14-month life expectancy, I realized that I wasn’t getting sicker; I was getting better.”

Demarest credits her music with what some might call a miracle. “I think it’s the getting back to my music that really changed my body chemistry,” says Demarest, adding that she guesses there will one day be evidence to show that music can improve a person’s immune system. Demarest’s cancer has been in remission for 10 years and counting.

Today, life is good. “I’m healthy, I work out … I feel great,” says Demarest cheerfully. The icing on the cake may be her recent win in the 1998 Portland Songwriters Association contest. She took top honors in the Blues/Jazz/R&B category with her song You Got Everything Girl. And she regularly plays gigs with her band, Good Company.

One upcoming concert has added resonance for Demarest: a benefit concert for Diana Shea, Portland woman currently undergoing treatment for breast cancer. The concert is being organized by Lynn Frances Anderson, who will perform along with Demarest and Good Company, Artis the Spoonman, Cindy Lou Banks, Mark Bosnian, Sandy Frye, and Sky in the Road.

“One of the things thatI think gets overlooked is the potentially devastating financial impact of having breast cancer,” says benefit organizer Anderson.

Demarest knows from experience how true that is. “When I had cancer … I lost everything,” Demarest recalls. “I was getting ready to buy a house. I’d worked evening shifts for years to save $7,000 to buy that house. Then I got that diagnosis and it was gone in a heartbeat.”

Aside from providing some financial assistance for Shea, Demarest says she hopes the emotional support for Shea will be at least as powerful. “All that matters is who your friends are,” says Demarest, recalling the things that made a difference during her own illness. “The fact that all these people are getting together I’m sure is very healing for her.”

Her own illness also taught Demarest about appreciating the present. She admits it’s a lesson she sometimes forgets; though her music serves to keep her grounded. A reggae-influenced song she recently wrote with Nola Wilken, Haven’t Got the Time, illustrates that point.

It includes the lyrics:

I wonder if might borrow a dime

I’ve got to make a phone call

that will take me back in time

I’ve got to change the way things are

I’ve got to find the moment

when things got so bizarre

(Copyright 1999 Quilted Lyrics Music, BMI)

To that, Demarest adds: “I’ve learned that the only moment you have is right now. The most important thing is to be here and present. I don’t always succeed at that, but my most peaceful moments are when I’m in the present.”

The Portland Tribune

MUSIC TWINES THROUGH A LIFE OF SECOND CHANCES

-By Janine Robben, September 2001

Once a singing nun and now a cycle-riding cancer survivor, Theresa Demarest just wants to rock.Theresa Demarest has been a nun, wife, mother, half of a hippie musical duo, single parent, critical-care nurse, cancer survivor, motorcycle mama. But, most important, she’s a singer with a bluesy-folksy-jazzy voice that picks up the high and low notes of each of her experiences and reproduces them with perfect clarity – like a really  great sound system.

great sound system.

Theresa Demarest & Good Company will perform at 3:15 p.m. Sunday at ProSounds 2001, a Labor Day music festival presented by the American Federation of Musicians Local No. 99 at Pioneer Courthouse Square. The band’s music has been termed ‘eclectic’ – a word that summarizes Demarest’s life as well.

As a teen-ager in the 1960’s, Demarest joined the Sisters of Mercy, a nursing and teaching order based in Nebraska. She brought to the order two things: her guitar and an intense desire to be a nurse. But her superiors – perhaps failing to see the spiritual side of “California Dreamin'” and “Wipe Out” – labeled her disobedient for failing to give up her possession and persona from the secular world. They made her a teacher instead of a nurse.

After several years Demarest left the Sisters of Mercy, “disobedient” but not so disobedient that she wouldn’t first sit through a three-week program intended to make her change her mind. “The whole time I could have just gotten up and left,” she says, her voice in midlife betraying a hint of wonder that she didn’t.

She returned to her native California and, within six months, met Tom Demarest in a music store. “I was so quiet,” she says. “A convent is a very quiet, meditative place.” She must have been bowled over by Demarest, who used the guitar she had left at the store for repair to track down her name and address. He took her to a Peter, Paul and Mary concert, which was, she remembers thinking, “the right thing to do.”

Together they moved to Corvallis, where he attended college and she gave birth to their son, Joshua, for whom her current record label is named. They lived on food stamps and performed together as Tom and Theresa in a local club for $15 a night.

Eventually, their fee soared to an average of $150 a night plus tips: “Back then, that was really a good living.” But their marriage bottomed out, and Demarest, now a single parent with shared custody of Joshua, finally went to nursing school.

Healer, Heal Thyself

She was a nurse when medicine began to dominate her personal as well as professional life. In 1983 she was diagnosed with breast cancer, which a Portland area hospital treated with surgery and chemotherapy. Her physicians, feeling the pain of having recently lost several patients of her age to the same kind of cancer, braced themselves against a repeat experience.

“We’ve given you everything we can,” Demarest says the doctors told her when she finished chemotherapy.”There’s nothing more we can do to treat you. If it comes back, don’t come back here.”

Five years later, on the cusp of being pronounced cured, Demarest¹s cancer returned. This time she was a patient at the hospital then called Oregon Health Sciences University, where she was working as a critical-care nurse, and this time the prognosis was blunt and hopeless: 14 months.

She received radiation therapy.”They had a radiation machine that took up this whole room,” she says. “Interns were in like buzzards, only 14 months to live. But then this old guy came in, and he was old, and he said, “don’t you listen to anyone, you’re going to be OK.”

Demarest supplemented the radiation with her own treatment regime. “I did everything,” she says. “I stayed up in the middle of the night, I didn’t stay up in the middle of the night. I read poetry, I didn’t read poetry. I drank, I didn’t drink.”

Something worked: Thirteen years later, Demarest is cancer-free. And that 14-months-to-live diagnosis? “We really gave you six months,” she says her doctor told her later. “I don’t know where you got 14.”

Time to Move On

It’s been four years since Demarest realized that she needed to leave nursing, but she still tears up at the memory of the patient who triggered her decision.

He was 18, his right arm mangled in an accident with some boating equipment, the amputated stub hanging in traction above his bed at OHSU, where Demarest was working in a recovery unit. “Were they able to save my arm?” he asked her, even though he could see – anyone could see – that his forearm was gone.

In 11 years as a critical-care nurse, Demarest had seen worse trauma, and patients whose injuries were going to affect their futures much more than the loss of his arm would affect this young man.

But, like Hawkeye Pierce in the “MASH” episode in which he dreams of rowing through a sea of body parts, she’d seen enough. “It’s kind of like that,” she says, still sounding weary. “Time to get out.”

So she added nursing to the eclectic life experiences on which she now muses.

Religion? “I spent years looking for the right church,” she says of her post-convent life. “All that formal religious stuff. Just like critical-care nursing; one day it’s just gone. But I have a very strong, very spiritual life.”

Playing in bars? “I don’t want to play the bars anymore,” she says firmly. “Two nights in Seattle, two nights in Portland, two nights in Corvallis, then you start over.”

Cancer? “I’ve had so many leases on my life,” she rejoices; these days the former trauma nurse is enamored of riding motorcycles.

And she has a music career that is, finally, almost a full-time gig. “Every musician in Portland has a day job,” she says, adding that she’s been told Portland has the highest per capita rate of musicians in the country.

It’s a competitive field in which Demarest is definitely a player. In 1995 she formed a record label, Joshua Records. She’s recorded a number of CDs and plays with some big names in the Portland music scene.

The Good Company band performing Sunday will include Theo Burke on piano, Renato Caranto on saxophone, Kevin Deitz on bass, Tim Ellis on guitar and Ward Griffiths on drums. But on another night, listeners might hear the regular Good Company lineup of Ellis and Grammy Award nominee Janice Scroggins with drummer Byron Mercurius: bassists Deitz, Jim Solberg, Jo Conrad or Sandin Wilson (Swingline Clubs); and saxophonists Caranto or Patrick Lamb (Patrick Lamb Band).

The Good Company band performing Sunday will include Theo Burke on piano, Renato Caranto on saxophone, Kevin Deitz on bass, Tim Ellis on guitar and Ward Griffiths on drums. But on another night, listeners might hear the regular Good Company lineup of Ellis and Grammy Award nominee Janice Scroggins with drummer Byron Mercurius: bassists Deitz, Jim Solberg, Jo Conrad or Sandin Wilson (Swingline Clubs); and saxophonists Caranto or Patrick Lamb (Patrick Lamb Band).

Last year Theresa Demarest and Good Company took a grant-funded “Keiko¹s Dream tour” through local schools. One of the numbers they played uses instruments to mimic the sounds of a whale. “There’s a third section where it gets louder and really takes off, where the kids at Boise-Eliot (Elementary School) stood up and started clapping,” Demarest says. “They clapped all the way to the end of the piece.”

Theresa Demarest as teacher instead of nurse? Maybe the Sisters of Mercy had her pegged right, after all.

Citysearch

Demarest’s Strongest Effort Yet

– Curtis Waterbury, A&E Editor, City Search: Music Section , 2001

After 20 years in Portland’s music scene, Theresa Demarest may be best-known to locals as a folk musician. Since the 1996 expansion of her band, Good Company, to include the current lineup, Demarest’s sound has broadened and become pleasantly diverse and worldly. Recorded live at the Portland Center for Performing Arts, “Keiko’s Dream” has the local singer-songwriter dipping her feet into a variety of musical pools to raise money for the Ocean Futures Society. The result: Demarest’s strongest effort yet.

Demarest has always crafted a good song—her unique rhythm guitar work, country-style vocals and endearing lyrics blend together perfectly. Now we get a taste of what Demarest has been working toward for the past three years with Good Company, and how she’s setting her sights on more than just neo-folk.

Guitarist Tim Ellis stands out on this album. His music blends perfectly with Chata Addy’s talking drum on “Moon Rising,” breathing fresh air into one of Demerest’s older songs. Ellis really shines, though, on the title instrumental track, with six minutes of searing, spacey guitar solos. Pianist Janice Scroggins fills in the spaces on Demarest’s folk ballads with an airy, synthesized quality, then turns around and jumps into such jazzy instrumentals as “She Arose.” Scroggins floats along, hitting some beautiful minor chords backed by Addy’s congas, then delves into some true pounding blues riffs.

Most songs on this release have an ethereal quality, but vocalist Myrtle Brown contributes a healthy dose of straight-up blues. Brown lets loose on the piano blues number, “Meet Me With Your Black Drawers On” and gets a little help from Scroggins tickling the ivories and Dennis Springer blowing a soulful sax. It’s a powerful reminder that Brown’s one of the region’s best blues singers. Demarest herself veers away from the album’s mellow side when she lays into the subsequent ragtime tune, “Sunshine,” with passion.

Most songs on this release have an ethereal quality, but vocalist Myrtle Brown contributes a healthy dose of straight-up blues. Brown lets loose on the piano blues number, “Meet Me With Your Black Drawers On” and gets a little help from Scroggins tickling the ivories and Dennis Springer blowing a soulful sax. It’s a powerful reminder that Brown’s one of the region’s best blues singers. Demarest herself veers away from the album’s mellow side when she lays into the subsequent ragtime tune, “Sunshine,” with passion.

Besides the great infusion of jazz, blues and folk, “Keiko’s Dream” also represents the next step in this local singer-songwriter’s evolving career. Good Company indeed.

Citysearch Entry – I HAVE FOUND MY VOICE

“I have found my voice, and its song paves a sure path” – Theresa Demarest, 1998

I’ve struggled with breast cancer twice. So, the way I see it, I’ve had two wake-up calls – two invitations to figure out just who I am and why I’m here. We all have subtle invitations like that each day, but we often don’t pay attention to them. It’s just human nature, I guess.

The first time I heard about breast cancer, I was in an anatomy and physiology lecture in nursing school. The lump in my breast seemed to fit the description I’d heard in class. But I’d just read some studies about nursing and medical students’ tendency to believe that they have nearly every disease they study, so I didn’t go to the doctor to have it looked at. When I finally did see the doctor, several months later, it was 2cm x 4cm 6 cm too big.

After a year of chemotherapy treatment and recovery, I returned to school and became a critical care nurse. Music had always been my life’s passion, and I was pursuing that dream on the side. I was getting ready to buy my first house. My son was doing well in high school. Things were good.

But then, one morning, there it was. A tumor in my chest. Just sitting there. I could feel it – immovable, with irregular edges. Big. Ugly. Terrifying. I took a friend to the doctor with me. I didn’t want to hear what I already knew. There was no question about it: my breast cancer had metastasized into my chest wall. The doctor diagnosed me with a life expectancy of 14 months and scheduled surgery for the very next day.

No one knows until it happens to you what it’s like to have death wrapped around your face and your body 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It forces a sure-fire, single-mindedness, or despair. For me, there was no in-between.

I figured that if I’ve only got a year, then I’m going to get back to my music. I wanted something permanent to leave with my son. I wrote a song for him and called it ‘Being who You Are’. It became the title tune for the CD I released after that year. Seven months into my 14-month life expectancy, I realized that I wasn’t getting sicker; I was getting better. Singing made me happy and that changed my body chemistry and my priorities.

My time on this planet and what I chose to do with it have become my most valuable treasures. I will never forget that being alive is actually a privilege, and that it comes with the challenge of figuring out why we are here. I think that’s true for everyone, whether or not a life-threatening illness is involved. I can’t help but believe that getting back to my music was one of the most important decisions I made. I have found my voice and its song paves a sure path.